Inside: Animal poems for the animal people in the room. There’s a lot of us, myself included, and I love any art pieces that pertain to cute little animals.

I consider myself an animal person for sure. Not really a pet person, because I don’t care for the hair and the feeding schedule (I’m really trying to keep myself fed, let alone another being!)

Animals are some of the sweetest most caring beings in the world, they truly care about us and the planet more than we do– it’s their instinct to protect their habitat! Not to mention there are so many characteristics of all of the different kinds of animals in the world that we can learn from. As they move through life with instinct and nature, they only create positive impacts on the world around them.

I want to be more like animals, naturally taking care of everything around me. So I want to read pieces of art and poetry about them, and while some are simply fun and light hearted, I want to know what lessons there are to learn from some of them to take on their characteristics.

What Do Animals Represent In Poetry

As with everything in nature, animals do carry symbolism and representation to deeper meanings of our lives. Nature, while its main goal is to carry on and continue being a place for us to live and thrive, also serves as many reminders to think about life deeper and more meaningfully.

As you read poetry that includes animals, sometimes it won’t even mention the deeper meaning behind the species and the animals themselves, but there’s a culturally deeper understanding to what they stand for. “If you know, you know” kind of situation if you will.

In most cultures, animals represent life, vitality, and fertility. You see in old cultural texts how animals were symbols of spirituality and gods, and this has translated to more of a sign of life and liveliness.

The symbolism and meaning behind different animals can be found in their most obvious traits. Like bears are strong so they symbolize strength, and beavers are known to be hard workers and creating something out of nothing, so they’re a reminder to keep up the hard work. It’s rewarding.

So as you evaluate and really consider what different animals mean and how they can be important in the poem you’re reading, consider what their main and most relevant traits are, and you might find it. Or something else that you can evaluate and appreciate about the animal.

How To Use These Poems

Poetry is all about being read, pondered, and consumed. It’s not all about the use of them.

But if you have a child’s birthday party that’s animal themed, some of these animal poems are perfect for writing in a card to the birthday boy or girl, or writing on the invitations if you’re the one hosting.

If you’re a teacher taking a field trip to the zoo, these could be fun for classroom activities, or if you’re reading some of the more serious and deeper poems, these can just simply be used to learn more about our lives through animals.

Animal Poetry

1. The Eagle

He clasps the crag with crooked hands;

Close to the sun in lonely lands,

Ringed with the azure world, he stands.

The wrinkled sea beneath him crawls;

He watches from his mountain walls,

And like a thunderbolt he falls.

2. The Crocodile

How doth the little crocodile

Improve his shining tail,

And pour the waters of the Nile

On every golden scale!

How cheerfully he seems to grin,

How neatly spreads his claws,

And welcomes little fishes in,

With gently smiling jaws!

3. Leda and the Swan

A sudden blow: the great wings beating still

Above the staggering girl, her thighs caressed

By the dark webs, her nape caught in his bill,

He holds her helpless breast upon his breast.

How can those terrified vague fingers push

The feathered glory from her loosening thighs?

And how can body, laid in that white rush,

But feel the strange heart beating where it lies?

A shudder in the loins engenders there

The broken wall, the burning roof and tower

And Agamemnon dead.

Being so caught up,

So mastered by the brute blood of the air,

Did she put on his knowledge with his power

Before the indifferent beak could let her drop?

4. The Armadillo

For Robert Lowell

This is the time of year

when almost every night

the frail, illegal fire balloons appear.

Climbing the mountain height,

rising toward a saint

still honored in these parts,

the paper chambers flush and fill with light

that comes and goes, like hearts.

Once up against the sky it’s hard

to tell them from the stars—

planets, that is—the tinted ones:

Venus going down, or Mars,

or the pale green one. With a wind,

they flare and falter, wobble and toss;

but if it’s still they steer between

the kite sticks of the Southern Cross,

receding, dwindling, solemnly

and steadily forsaking us,

or, in the downdraft from a peak,

suddenly turning dangerous.

Last night another big one fell.

It splattered like an egg of fire

against the cliff behind the house.

The flame ran down. We saw the pair

of owls who nest there flying up

and up, their whirling black-and-white

stained bright pink underneath, until

they shrieked up out of sight.

The ancient owls’ nest must have burned.

Hastily, all alone,

a glistening armadillo left the scene,

rose-flecked, head down, tail down,

and then a baby rabbit jumped out,

short-eared, to our surprise.

So soft!—a handful of intangible ash

with fixed, ignited eyes.

Too pretty, dreamlike mimicry!

O falling fire and piercing cry

and panic, and a weak mailed fist

clenched ignorant against the sky!

5. The Dusk of Horses

Right under their noses, the green

Of the field is paling away

Because of something fallen from the sky.

They see this, and put down

Their long heads deeper in grass

That only just escapes reflecting them

As the dream of a millpond would.

The color green flees over the grass

Like an insect, following the red sun over

The next hill. The grass is white.

There is no cloud so dark and white at once;

There is no pool at dawn that deepens

Their faces and thirsts as this does.

Now they are feeding on solid

Cloud, and, one by one,

With nails as silent as stars among the wood

Hewed down years ago and now rotten,

The stalls are put up around them.

Now if they lean, they come

On wood on any side. Not touching it, they sleep.

No beast ever lived who understood

What happened among the sun’s fields,

Or cared why the color of grass

Fled over the hill while he stumbled,

Led by the halter to sleep

On his four taxed, worthy legs.

Each thinks he awakens where

The sun is black on the rooftop,

That the green is dancing in the next pasture,

And that the way to sleep

In a cloud, or in a risen lake,

Is to walk as though he were still

in the drained field standing, head down,

To pretend to sleep when led,

And thus to go under the ancient white

Of the meadow, as green goes

And whiteness comes up through his face

Holding stars and rotten rafters,

Quiet, fragrant, and relieved.

6. The Bear

1

In late winter

I sometimes glimpse bits of steam

coming up from

some fault in the old snow

and bend close and see it is lung-colored

and put down my nose

and know

the chilly, enduring odor of bear.

2

I take a wolf’s rib and whittle

it sharp at both ends

and coil it up

and freeze it in blubber and place it out

on the fairway of the bears.

And when it has vanished

I move out on the bear tracks,

roaming in circles

until I come to the first, tentative, dark

splash on the earth.

And I set out

running, following the splashes

of blood wandering over the world.

At the cut, gashed resting places

I stop and rest,

at the crawl-marks

where he lay out on his belly

to overpass some stretch of bauchy ice

I lie out

dragging myself forward with bear-knives in my fists.

3

On the third day I begin to starve,

at nightfall I bend down as I knew I would

at a turd sopped in blood,

and hesitate, and pick it up,

and thrust it in my mouth, and gnash it down,

and rise

and go on running.

4

On the seventh day,

living by now on bear blood alone,

I can see his upturned carcass far out ahead, a scraggled,

steamy hulk,

the heavy fur riffling in the wind.

I come up to him

and stare at the narrow-spaced, petty eyes,

the dismayed

face laid back on the shoulder, the nostrils

flared, catching

perhaps the first taint of me as he

died.

I hack

a ravine in his thigh, and eat and drink,

and tear him down his whole length

and open him and climb in

and close him up after me, against the wind,

and sleep.

5

And dream

of lumbering flatfooted

over the tundra,

stabbed twice from within,

splattering a trail behind me,

splattering it out no matter which way I lurch,

no matter which parabola of bear-transcendence,

which dance of solitude I attempt,

which gravity-clutched leap,

which trudge, which groan.

6

Until one day I totter and fall—

fall on this

stomach that has tried so hard to keep up,

to digest the blood as it leaked in,

to break up

and digest the bone itself: and now the breeze

blows over me, blows off

the hideous belches of ill-digested bear blood

and rotted stomach

and the ordinary, wretched odor of bear,

blows across

my sore, lolled tongue a song

or screech, until I think I must rise up

and dance. And I lie still.

7

I awaken I think. Marshlights

reappear, geese

come trailing again up the flyway.

In her ravine under old snow the dam-bear

lies, licking

lumps of smeared fur

and drizzly eyes into shapes

with her tongue. And one

hairy-soled trudge stuck out before me,

the next groaned out,

the next,

the next,

the rest of my days I spend

wandering: wondering

what, anyway,

was that sticky infusion, that rank flavor of blood, that poetry, by which I lived?

7. Baby Tortoise

You know what it is to be born alone,

Baby tortoise!

The first day to heave your feet little by little from

the shell,

Not yet awake,

And remain lapsed on earth,

Not quite alive.

A tiny, fragile, half-animate bean.

To open your tiny beak-mouth, that looks as if it would

never open

Like some iron door;

To lift the upper hawk-beak from the lower base

And reach your skinny neck

And take your first bite at some dim bit of herbage,

Alone, small insect,

Tiny bright-eye,

Slow one.

To take your first solitary bite

And move on your slow, solitary hunt.

Your bright, dark little eye,

Your eye of a dark disturbed night,

Under its slow lid, tiny baby tortoise,

So indomitable.

No one ever heard you complain.

You draw your head forward, slowly, from your little

wimple

And set forward, slow-dragging, on your four-pinned toes,

Rowing slowly forward.

Wither away, small bird?

Rather like a baby working its limbs,

Except that you make slow, ageless progress

And a baby makes none.

The touch of sun excites you,

And the long ages, and the lingering chill

Make you pause to yawn,

Opening your impervious mouth,

Suddenly beak-shaped, and very wide, like some suddenly

gaping pincers;

Soft red tongue, and hard thin gums,

Then close the wedge of your little mountain front,

Your face, baby tortoise.

Do you wonder at the world, as slowly you turn your head

in its wimple

And look with laconic, black eyes?

Or is sleep coming over you again,

The non-life?

You are so hard to wake.

Are you able to wonder?

Or is it just your indomitable will and pride of the

first life

Looking round

And slowly pitching itself against the inertia

Which had seemed invincible?

The vast inanimate,

And the fine brilliance of your so tiny eye,

Challenger.

Nay, tiny shell-bird.

What a huge vast inanimate it is, that you must row

against,

What an incalculable inertia.

Challenger,

Little Ulysses, fore-runner,

No bigger than my thumb-nail,

Buon viaggio.

All animate creation on your shoulder,

Set forth, little Titan, under your battle-shield.

The ponderous, preponderate,

Inanimate universe;

And you are slowly moving, pioneer, you alone.

How vivid your travelling seems now, in the troubled

sunshine,

Stoic, Ulyssean atom;

Suddenly hasty, reckless, on high toes.

Voiceless little bird,

Resting your head half out of your wimple

In the slow dignity of your eternal pause.

Alone, with no sense of being alone,

And hence six times more solitary;

Fulfilled of the slow passion of pitching through

immemorial ages

Your little round house in the midst of chaos.

Over the garden earth,

Small bird,

Over the edge of all things.

Traveller,

With your tail tucked a little on one side

Like a gentleman in a long-skirted coat.

All life carried on your shoulder,

Invincible fore-runner.

8. The Lamb

Little lamb, who made thee?

Dost thou know who made thee,

Gave thee life, and bid thee feed

By the stream and o’er the mead;

Gave thee clothing of delight,

Softest clothing, woolly, bright;

Gave thee such a tender voice,

Making all the vales rejoice?

Little lamb, who made thee?

Dost thou know who made thee?

Little lamb, I’ll tell thee;

Little lamb, I’ll tell thee:

He is called by thy name,

For He calls Himself a Lamb.

He is meek, and He is mild,

He became a little child.

I a child, and thou a lamb,

We are called by His name.

Little lamb, God bless thee!

Little lamb, God bless thee!

9. The Fly

Little fly,

Thy summer’s play

My thoughtless hand

Has brushed away.

Am not I

A fly like thee?

Or art not thou

A man like me?

For I dance

And drink and sing,

Till some blind hand

Shall brush my wing.

If thought is life

And strength and breath,

And the want

Of thought is death,

Then am I

A happy fly,

If I live,

Or if I die.

10. I Am! Said the Lamb [excerpt]

The Donkey

I had a Donkey, that was all right,

But he always wanted to fly my Kite;

Every time I let him, the String would bust.

Your Donkey is better behaved, I trust.

The Ceiling

Suppose the Ceiling went Outside

And then caught Cold and Up and Died?

The only Thing we’d have for Proof

That he was Gone, would be the Roof;

I think it would be Most Revealing

To find out how the Ceiling’s Feeling.

The Chair

A funny thing about a Chair:

You hardly ever think it’s there.

To know a Chair is really it,

You sometimes have to go and sit.

The Hippo

A Head or Tail—which does he lack?

I think his Forward’s coming back!

He lives on Carrots, Leeks and Hay;

He starts to yawn—it takes All Day—

Some time I think I’ll live that way.

The Lizard

The Time to Tickle a Lizard,

Is Before, or Right After, a Blizzard.

Now the place to begin

Is just under his Chin,—

And here’s more Advice:

Don’t Poke more than Twice

At an Intimate Place like his Gizzard.

11. Woodchucks

Gassing the woodchucks didn’t turn out right.

The knockout bomb from the Feed and Grain Exchange

was featured as merciful, quick at the bone

and the case we had against them was airtight,

both exits shoehorned shut with puddingstone,

but they had a sub-sub-basement out of range.

Next morning they turned up again, no worse

for the cyanide than we for our cigarettes

and state-store Scotch, all of us up to scratch.

They brought down the marigolds as a matter of course

and then took over the vegetable patch

nipping the broccoli shoots, beheading the carrots.

The food from our mouths, I said, righteously thrilling

to the feel of the .22, the bullets’ neat noses.

I, a lapsed pacifist fallen from grace

puffed with Darwinian pieties for killing,

now drew a bead on the little woodchuck’s face.

He died down in the everbearing roses.

Ten minutes later I dropped the mother. She

flipflopped in the air and fell, her needle teeth

still hooked in a leaf of early Swiss chard.

Another baby next. O one-two-three

the murderer inside me rose up hard,

the hawkeye killer came on stage forthwith.

There’s one chuck left. Old wily fellow, he keeps

me cocked and ready day after day after day.

All night I hunt his humped-up form. I dream

I sight along the barrel in my sleep.

If only they’d all consented to die unseen

gassed underground the quiet Nazi way.

12. The Moose

For Grace Bulmer Bowers

From narrow provinces

of fish and bread and tea,

home of the long tides

where the bay leaves the sea

twice a day and takes

the herrings long rides,

where if the river

enters or retreats

in a wall of brown foam

depends on if it meets

the bay coming in,

the bay not at home;

where, silted red,

sometimes the sun sets

facing a red sea,

and others, veins the flats’

lavender, rich mud

in burning rivulets;

on red, gravelly roads,

down rows of sugar maples,

past clapboard farmhouses

and neat, clapboard churches,

bleached, ridged as clamshells,

past twin silver birches,

through late afternoon

a bus journeys west,

the windshield flashing pink,

pink glancing off of metal,

brushing the dented flank

of blue, beat-up enamel;

down hollows, up rises,

and waits, patient, while

a lone traveller gives

kisses and embraces

to seven relatives

and a collie supervises.

Goodbye to the elms,

to the farm, to the dog.

The bus starts. The light

grows richer; the fog,

shifting, salty, thin,

comes closing in.

Its cold, round crystals

form and slide and settle

in the white hens’ feathers,

in gray glazed cabbages,

on the cabbage roses

and lupins like apostles;

the sweet peas cling

to their wet white string

on the whitewashed fences;

bumblebees creep

inside the foxgloves,

and evening commences.

One stop at Bass River.

Then the Economies

Lower, Middle, Upper;

Five Islands, Five Houses,

where a woman shakes a tablecloth

out after supper.

A pale flickering. Gone.

The Tantramar marshes

and the smell of salt hay.

An iron bridge trembles

and a loose plank rattles

but doesn’t give way.

On the left, a red light

swims through the dark:

a ship’s port lantern.

Two rubber boots show,

illuminated, solemn.

A dog gives one bark.

A woman climbs in

with two market bags,

brisk, freckled, elderly.

“A grand night. Yes, sir,

all the way to Boston.”

She regards us amicably.

Moonlight as we enter

the New Brunswick woods,

hairy, scratchy, splintery;

moonlight and mist

caught in them like lamb’s wool

on bushes in a pasture.

The passengers lie back.

Snores. Some long sighs.

A dreamy divagation

begins in the night,

a gentle, auditory,

slow hallucination. . . .

In the creakings and noises,

an old conversation

–not concerning us,

but recognizable, somewhere,

back in the bus:

Grandparents’ voices

uninterruptedly

talking, in Eternity:

names being mentioned,

things cleared up finally;

what he said, what she said,

who got pensioned;

deaths, deaths and sicknesses;

the year he remarried;

the year (something) happened.

She died in childbirth.

That was the son lost

when the schooner foundered.

He took to drink. Yes.

She went to the bad.

When Amos began to pray

even in the store and

finally the family had

to put him away.

“Yes . . .” that peculiar

affirmative. “Yes . . .”

A sharp, indrawn breath,

half groan, half acceptance,

that means “Life’s like that.

We know it (also death).”

Talking the way they talked

in the old featherbed,

peacefully, on and on,

dim lamplight in the hall,

down in the kitchen, the dog

tucked in her shawl.

Now, it’s all right now

even to fall asleep

just as on all those nights.

–Suddenly the bus driver

stops with a jolt,

turns off his lights.

A moose has come out of

the impenetrable wood

and stands there, looms, rather,

in the middle of the road.

It approaches; it sniffs at

the bus’s hot hood.

Towering, antlerless,

high as a church,

homely as a house

(or, safe as houses).

A man’s voice assures us

“Perfectly harmless. . . .”

Some of the passengers

exclaim in whispers,

childishly, softly,

“Sure are big creatures.”

“It’s awful plain.”

“Look! It’s a she!”

Taking her time,

she looks the bus over,

grand, otherworldly.

Why, why do we feel

(we all feel) this sweet

sensation of joy?

“Curious creatures,”

says our quiet driver,

rolling his r’s.

“Look at that, would you.”

Then he shifts gears.

For a moment longer,

by craning backward,

the moose can be seen

on the moonlit macadam;

then there’s a dim

smell of moose, an acrid

smell of gasoline.

13. The Tyger

Tyger! Tyger! burning bright

In the forests of the night,

What immortal hand or eye

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

In what distant deeps or skies

Burnt the fire of thine eyes?

On what wings dare he aspire?

What the hand, dare sieze the fire?

And what shoulder, & what art,

Could twist the sinews of thy heart?

And when thy heart began to beat,

What dread hand? & what dread feet?

What the hammer? what the chain?

In what furnace was thy brain?

What the anvil? what dread grasp

Dare its deadly terrors clasp?

When the stars threw down their spears,

And water’d heaven with their tears,

Did he smile his work to see?

Did he who made the Lamb make thee?

Tyger! Tyger! burning bright

In the forests of the night,

What immortal hand or eye

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?

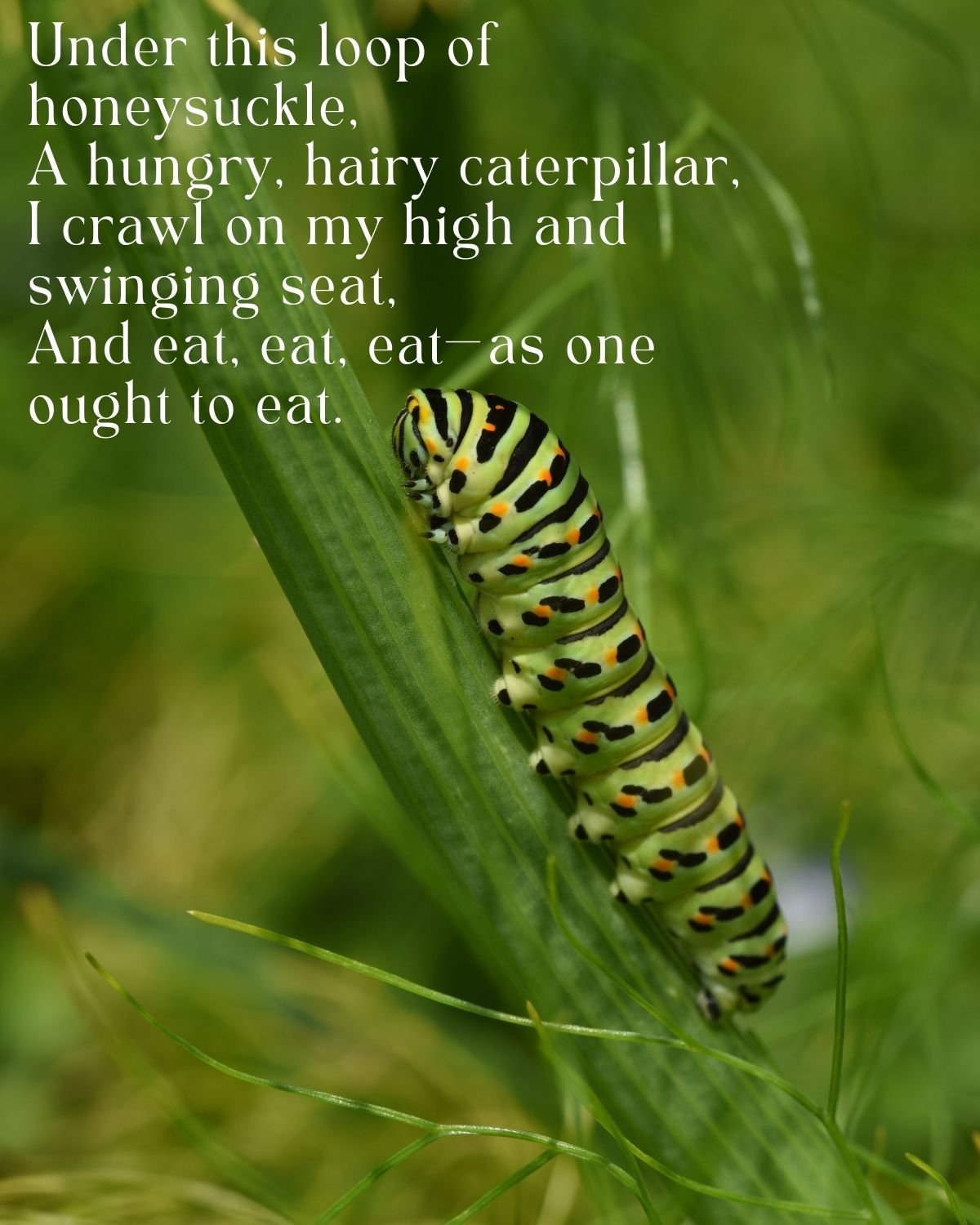

14. The Caterpillar – an animal poem about transformation

Under this loop of honeysuckle,

A creeping, coloured caterpillar,

I gnaw the fresh green hawthorn spray,

I nibble it leaf by leaf away.

Down beneath grow dandelions,

Daisies, old-man’s-looking-glasses;

Rooks flap croaking across the lane.

I eat and swallow and eat again.

Here come raindrops helter-skelter;

I munch and nibble unregarding:

Hawthorn leaves are juicy and firm.

I’ll mind my business: I’m a good worm.

When I’m old, tired, melancholy,

I’ll build a leaf-green mausoleum

Close by, here on this lovely spray,

And die and dream the ages away.

Some say worms win resurrection,

With white wings beating flitter-flutter,

But wings or a sound sleep, why should I care?

Either way I’ll miss my share.

Under this loop of honeysuckle,

A hungry, hairy caterpillar,

I crawl on my high and swinging seat,

And eat, eat, eat—as one ought to eat.

Fun Animal Poems

15. The Chambered Nautilus

This is the ship of pearl, which, poets feign,

Sails the unshadowed main,

The venturous bark that flings

On the sweet summer wind its purpled wings

In gulfs enchanted, where the Siren sings,

And coral reefs lie bare,

Where the cold sea-maids rise to sun their streaming hair.

Its webs of living gauze no more unfurl;

Wrecked is the ship of pearl!

And every chambered cell,

Where its dim dreaming life was wont to dwell,

As the frail tenant shaped his growing shell,

Before thee lies revealed,

Its irised ceiling rent, its sunless crypt unsealed!

Year after year beheld the silent toil

That spread his lustrous coil;

Still, as the spiral grew,

He left the past year’s dwelling for the new,

Stole with soft step its shining archway through,

Built up its idle door,

Stretched in his last-found home, and knew the old no more.

Thanks for the heavenly message brought by thee,

Child of the wandering sea,

Cast from her lap, forlorn!

From thy dead lips a clearer note is born

Than ever Triton blew from wreathéd horn!

While on mine ear it rings,

Through the deep caves of thought I hear a voice that sings:

Build thee more stately mansions, O my soul,

As the swift seasons roll!

Leave thy low-vaulted past!

Let each new temple, nobler than the last,

Shut thee from heaven with a dome more vast,

Till thou at length art free,

Leaving thine outgrown shell by life’s unresting sea!

16. The Walrus and the Carpenter

The sun was shining on the sea,

Shining with all his might:

He did his very best to make

The billows smooth and bright—

And this was odd, because it was

The middle of the night.

The moon was shining sulkily,

Because she thought the sun

Had got no business to be there

After the day was done—

“It’s very rude of him,” she said,

“To come and spoil the fun!”

The sea was wet as wet could be,

The sands were dry as dry.

You could not see a cloud because

No cloud was in the sky:

No birds were flying overhead—

There were no birds to fly.

The Walrus and the Carpenter

Were walking close at hand:

They wept like anything to see

Such quantities of sand:

“If this were only cleared away,”

They said, “it would be grand!”

“If seven maids with seven mops

Swept it for half a year,

Do you suppose,” the Walrus said,

“That they could get it clear?”

“I doubt it,” said the Carpenter,

And shed a bitter tear.

“0 Oysters, come and walk with us!”

The Walrus did beseech.

“A pleasant walk, a pleasant talk,

Along the briny beach:

We cannot do with more than four,

To give a hand to each.”

The eldest Oyster looked at him,

But never a word he said;

The eldest Oyster winked his eye,

And shook his heavy head—

Meaning to say he did not choose

To leave the oyster-bed.

But four young Oysters hurried up,

All eager for the treat:

Their coats were brushed, their faces washed,

Their shoes were clean and neat—

And this was odd, because, you know,

They hadn’t any feet.

Four other Oysters followed them,

And yet another four;

And thick and fast they came at last,

And more and more and more—

All hopping through the frothy waves,

And scrambling to the shore.

The Walrus and the Carpenter

Walked on a mile or so,

And then they rested on a rock

Conveniently low:

And all the little Oysters stood

And waited in a row.

“The time has come,” the Walrus said,

“To talk of many things:

Of shoes—and ships—and sealing-wax—

Of cabbages—and kings—

And why the sea is boiling hot—

And whether pigs have wings.”

“But wait a bit,” the Oysters cried,

“Before we have our chat;

For some of us are out of breath,

And all of us are fat!”

“No hurry!” said the Carpenter.

They thanked him much for that.

“A loaf of bread,” the Walrus said,

“Is what we chiefly need:

Pepper and vinegar besides

Are very good indeed—

Now, if you’re ready, Oysters dear,

We can begin to feed.”

“But not on us!” the Oysters cried,

Turning a little blue.

“After such kindness, that would be

A dismal thing to do!”

“The night is fine,” the Walrus said,

“Do you admire the view?

“It was so kind of you to come!

And you are very nice!”

The Carpenter said nothing but

“Cut us another slice.

I wish you were not quite so deaf—

I’ve had to ask you twice!”

“It seems a shame,” the Walrus said,

“To play them such a trick.

After we’ve brought them out so far,

And made them trot so quick!”

The Carpenter said nothing but

“The butter’s spread too thick!”

“I weep for you,” the Walrus said:

“I deeply sympathize.”

With sobs and tears he sorted out

Those of the largest size,

Holding his pocket-handkerchief

Before his streaming eyes.

“0 Oysters,” said the Carpenter,

“You’ve had a pleasant run!

Shall we be trotting home again?”

But answer came there none—

And this was scarcely odd, because

They’d eaten every one.

17. Ode to a Nightingale

1.

My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains

My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk,

Or emptied some dull opiate to the drains

One minute past, and Lethe-wards had sunk:

‘Tis not through envy of thy happy lot,

But being too happy in thine happiness,—

That thou, light-winged Dryad of the trees,

In some melodious plot

Of beechen green, and shadows numberless,

Singest of summer in full-throated ease.

2.

O, for a draught of vintage! that hath been

Cool’d a long age in the deep-delved earth,

Tasting of Flora and the country green,

Dance, and Provencal song, and sunburnt mirth!

O for a beaker full of the warm South,

Full of the true, the blushful Hippocrene,

With beaded bubbles winking at the brim,

And purple-stained mouth;

That I might drink, and leave the world unseen,

And with thee fade away into the forest dim:

3.

Fade far away, dissolve, and quite forget

What thou among the leaves hast never known,

The weariness, the fever, and the fret

Here, where men sit and hear each other groan;

Where palsy shakes a few, sad, last gray hairs,

Where youth grows pale, and spectre-thin, and dies;

Where but to think is to be full of sorrow

And leaden-eyed despairs,

Where Beauty cannot keep her lustrous eyes,

Or new Love pine at them beyond to-morrow.

4.

Away! away! for I will fly to thee,

Not charioted by Bacchus and his pards,

But on the viewless wings of Poesy,

Though the dull brain perplexes and retards:

Already with thee! tender is the night,

And haply the Queen-Moon is on her throne,

Cluster’d around by all her starry Fays;

But here there is no light,

Save what from heaven is with the breezes blown

Through verdurous glooms and winding mossy ways.

5.

I cannot see what flowers are at my feet,

Nor what soft incense hangs upon the boughs,

But, in embalmed darkness, guess each sweet

Wherewith the seasonable month endows

The grass, the thicket, and the fruit-tree wild;

White hawthorn, and the pastoral eglantine;

Fast fading violets cover’d up in leaves;

And mid-May’s eldest child,

The coming musk-rose, full of dewy wine,

The murmurous haunt of flies on summer eves.

6.

Darkling I listen; and, for many a time

I have been half in love with easeful Death,

Call’d him soft names in many a mused rhyme,

To take into the air my quiet breath;

Now more than ever seems it rich to die,

To cease upon the midnight with no pain,

While thou art pouring forth thy soul abroad

In such an ecstasy!

Still wouldst thou sing, and I have ears in vain—

To thy high requiem become a sod.

7.

Thou wast not born for death, immortal Bird!

No hungry generations tread thee down;

The voice I hear this passing night was heard

In ancient days by emperor and clown:

Perhaps the self-same song that found a path

Through the sad heart of Ruth, when, sick for home,

She stood in tears amid the alien corn;

The same that oft-times hath

Charm’d magic casements, opening on the foam

Of perilous seas, in faery lands forlorn.

8.

Forlorn! the very word is like a bell

To toil me back from thee to my sole self!

Adieu! the fancy cannot cheat so well

As she is fam’d to do, deceiving elf.

Adieu! adieu! thy plaintive anthem fades

Past the near meadows, over the still stream,

Up the hill-side; and now ’tis buried deep

In the next valley-glades:

Was it a vision, or a waking dream?

Fled is that music:—Do I wake or sleep?

18. Evening Hawk

From plane of light to plane, wings dipping through

Geometries and orchids that the sunset builds,

Out of the peak’s black angularity of shadow, riding

The last tumultuous avalanche of

Light above pines and the guttural gorge,

The hawk comes.

His wing

Scythes down another day, his motion

Is that of the honed steel-edge, we hear

The crashless fall of stalks of Time.

The head of each stalk is heavy with the gold of our error.

Look! Look! he is climbing the last light

Who knows neither Time nor error, and under

Whose eye, unforgiving, the world, unforgiven, swings

Into shadow.

Long now,

The last thrush is still, the last bat

Now cruises in his sharp hieroglyphics. His wisdom

Is ancient, too, and immense. The star

Is steady, like Plato, over the mountain.

If there were no wind we might, we think, hear

The earth grind on its axis, or history

Drip in darkness like a leaking pipe in the cellar.

19. Hope is the thing with feathers (254)

Hope is the thing with feathers

That perches in the soul,

And sings the tune without the words,

And never stops at all,

And sweetest in the gale is heard;

And sore must be the storm

That could abash the little bird

That kept so many warm.

I’ve heard it in the chillest land,

And on the strangest sea;

Yet, never, in extremity,

It asked a crumb of me.v

Animal Poems About Keeping Them

20. The Woman at the Washington Zoo

The saris go by me from the embassies.

Cloth from the moon. Cloth from another planet.

They look back at the leopard like the leopard.

And I. . . .

this print of mine, that has kept its color

Alive through so many cleanings; this dull null

Navy I wear to work, and wear from work, and so

To my bed, so to my grave, with no

Complaints, no comment: neither from my chief,

The Deputy Chief Assistant, nor his chief–

Only I complain. . . . this serviceable

Body that no sunlight dyes, no hand suffuses

But, dome-shadowed, withering among columns,

Wavy beneath fountains–small, far-off, shining

In the eyes of animals, these beings trapped

As I am trapped but not, themselves, the trap,

Aging, but without knowledge of their age,

Kept safe here, knowing not of death, for death–

Oh, bars of my own body, open, open!

The world goes by my cage and never sees me.

And there come not to me, as come to these,

The wild beasts, sparrows pecking the llamas’ grain,

Pigeons settling on the bears’ bread, buzzards

Tearing the meat the flies have clouded. . . .

Vulture,

When you come for the white rat that the foxes left,

Take off the red helmet of your head, the black

Wings that have shadowed me, and step to me as man:

The wild brother at whose feet the white wolves fawn,

To whose hand of power the great lioness

Stalks, purring. . . .

You know what I was,

You see what I am: change me, change me!

21. World Below the Brine

The world below the brine,

Forests at the bottom of the sea, the branches and leaves,

Sea-lettuce, vast lichens, strange flowers and seeds, the thick tangle, openings, and pink turf,

Different colors, pale gray and green, purple, white, and gold, the play of light through the water,

Dumb swimmers there among the rocks,coral, gluten, grass, rushes, and the aliment of the swimmers,

Sluggish existences grazing there suspended, or slowly crawling close to the bottom,

The sperm-whale at the surface blowing air and spray, or disporting with his flukes,

The leaden-eyed shark, the walrus, the turtle, the hairy sea-leopard, and the sting-ray,

Passions there, wars, pursuits, tribes, sight in those ocean-depths, breathing that thick-breathing air, as so many do,

The change thence to the sight here, and to the subtle air breathed by beings like us who walk this sphere,

The change onward from ours to that of beings who walk other spheres.

22. Seal Lullaby

Oh! hush thee, my baby, the night is behind us,

And black are the waters that sparkled so green.

The moon, o’er the combers, looks downward to find us

At rest in the hollows that rustle between.

Where billow meets billow, there soft be thy pillow;

Ah, weary wee flipperling, curl at thy ease!

The storm shall not wake thee, nor shark overtake thee,

Asleep in the arms of the slow-swinging seas.

23. The Maldive Shark

About the Shark, phlegmatical one,

Pale sot of the Maldive sea,

The sleek little pilot-fish, azure and slim,

How alert in attendance be.

From his saw-pit of mouth, from his charnel of maw

They have nothing of harm to dread,

But liquidly glide on his ghastly flank

Or before his Gorgonian head;

Or lurk in the port of serrated teeth

In white triple tiers of glittering gates,

And there find a haven when peril’s abroad,

An asylum in jaws of the Fates!

They are friends; and friendly they guide him to prey,

Yet never partake of the treat—

Eyes and brains to the dotard lethargic and dull,

Pale ravener of horrible meat.

24. The Shark’s Parlor

Memory: I can take my head and strike it on a wall on Cumberland Island

Where the night tide came crawling under the stairs came up the first

Two or three steps and the cottage stood on poles all night

With the sea sprawled under it as we dreamed of the great fin circling

Under the bedroom floor. In daylight there was my first brassy taste of beer

And Payton Ford and I came back from the Glynn County slaughterhouse

With a bucket of entrails and blood. We tied one end of a hawser

To a spindling porch-pillar and rowed straight out of the house

Three hundred yards into the vast front yard of windless blue water

The rope out slithering its coil the two-gallon jug stoppered and sealed

With wax and a ten-foot chain leader a drop-forged shark-hook nestling.

We cast our blood on the waters the land blood easily passing

For sea blood and we sat in it for a moment with the stain spreading

Out from the boat sat in a new radiance in the pond of blood in the sea

Waiting for fins waiting to spill our guts also in the glowing water.

We dumped the bucket, and baited the hook with a run-over collie pup. The jug

Bobbed, trying to shake off the sun as a dog would shake off the sea.

We rowed to the house feeling the same water lift the boat a new way,

All the time seeing where we lived rise and dip with the oars.

We tied up and sat down in rocking chairs, one eye on the other responding

To the blue-eye wink of the jug. Payton got us a beer and we sat

All morning sat there with blood on our minds the red mark out

In the harbor slowly failing us then the house groaned the rope

Sprang out of the water splinters flew we leapt from our chairs

And grabbed the rope hauled did nothing the house coming subtly

Apart all around us underfoot boards beginning to sparkle like sand

Pulling out the tarred poles we slept propped-up on leaning to sea

As in land-wind crabs scuttling from under the floor as we took runs about

Two more porch-pillars and looked out and saw something a fish-flash

An almighty fin in trouble a moiling of secret forces a false start

Of water a round wave growing in the whole of Cumberland Sound the one ripple.

Payton took off without a word I could not hold him either

But clung to the rope anyway it was the whole house bending

Its nails that held whatever it was coming in a little and like a fool

I took up the slack on my wrist. The rope drew gently jerked I lifted

Clean off the porch and hit the water the same water it was in

I felt in blue blazing terror at the bottom of the stairs and scrambled

Back up looking desperately into the human house as deeply as I could

Stopping my gaze before it went out the wire screen of the back door

Stopped it on the thistled rattan the rugs I lay on and read

On my mother’s sewing basket with next winter’s socks spilling from it

The flimsy vacation furniture a bucktoothed picture of myself.

Payton came back with three men from a filling station and glanced at me

Dripping water inexplicable then we all grabbed hold like a tug-of-war.

We were gaining a little from us a cry went up from everywhere

People came running. Behind us the house filled with men and boys.

On the third step from the sea I took my place looking down the rope

Going into the ocean, humming and shaking off drops. A houseful

Of people put their backs into it going up the steps from me

Into the living room through the kitchen down the back stairs

Up and over a hill of sand across a dust road and onto a raised field

Of dunes we were gaining the rope in my hands began to be wet

With deeper water all other haulers retreated through the house

But Payton and I on the stairs drawing hand over hand on our blood

Drawing into existence by the nose a huge body becoming

A hammerhead rolling in beery shallows and I began to let up

But the rope strained behind me the town had gone

Pulling-mad in our house far away in a field of sand they struggled

They had turned their backs on the sea bent double some on their knees

The rope over their shoulders like a bag of gold they strove for the ideal

Esso station across the scorched meadow with the distant fish coming up

The front stairs the sagging boards still coming in up taking

Another step toward the empty house where the rope stood straining

By itself through the rooms in the middle of the air. “Pass the word,”

Payton said, and I screamed it “Let up, good God, let up!” to no one there.

The shark flopped on the porch, grating with salt-sand driving back in

The nails he had pulled out coughing chunks of his formless blood.

The screen door banged and tore off he scrambled on his tail slid

Curved did a thing from another world and was out of his element and in

Our vacation paradise cutting all four legs from under the dinner table

With one deep-water move he unwove the rugs in a moment throwing pints

Of blood over everything we owned knocked the buckteeth out of my picture

His odd head full of crashed jelly-glass splinters and radio tubes thrashing

Among the pages of fan magazines all the movie stars drenched in sea-blood

Each time we thought he was dead he struggled back and smashed

One more thing in all coming back to die three or four more times after death.

At last we got him out logrolling him greasing his sandpaper skin

With lard to slide him pulling on his chained lips as the tide came,

Tumbled him down the steps as the first night wave went under the floor.

He drifted off head back belly white as the moon. What could I do but buy

That house for the one black mark still there against death a forehead-

toucher in the room he circles beneath and has been invited to wreck?

Blood hard as iron on the wall black with time still bloodlike

Can be touched whenever the brow is drunk enough. All changes. Memory:

Something like three-dimensional dancing in the limbs with age

Feeling more in two worlds than one in all worlds the growing encounters.

25. The White Horse

The youth walks up to the white horse, to put its halter on

and the horse looks at him in silence.

They are so silent, they are in another world.

26. Mole

For weeks he’s tunneled his intricate need

Through the root-rich, fibrous, humoral dark,

Buckling up in zagged illegibles

The cuneiforms and cursives of a blind scribe.

Sleeved by soft earth, a slow reach knuckling,

Small tributaries open from his nudge—

Mild immigrant, bland isolationist,

Berm builder edging the runneling world.

But now the snow, and he’s gone quietly deep,

Nuzzling through a muzzy neighborhood

Of dead-end-street, abandoned cul-de-sac,

And boltrun from a dead-leaf, roundhouse burrow.

May he emerge four months from this as before,

Myopic master of the possible,

Wise one who understands prudential ground,

Revisionist of all things green;

So when he surfaces, lumplike, bashful,

Quizzical as the flashbulb blind who wait

For color to return, he’ll nose our green-

rich air with the imperative poise of now.

27. The Elephant is Slow to Mate

The elephant, the huge old beast,

is slow to mate;

he finds a female, they show no haste

they wait

for the sympathy in their vast shy hearts

slowly, slowly to rouse

as they loiter along the river-beds

and drink and browse

and dash in panic through the brake

of forest with the herd,

and sleep in massive silence, and wake

together, without a word.

So slowly the great hot elephant hearts

grow full of desire,

and the great beasts mate in secret at last,

hiding their fire.

Oldest they are and the wisest of beasts

so they know at last

how to wait for the loneliest of feasts

for the full repast.

They do not snatch, they do not tear;

their massive blood

moves as the moon-tides, near, more near

till they touch in flood.

28. The Fish

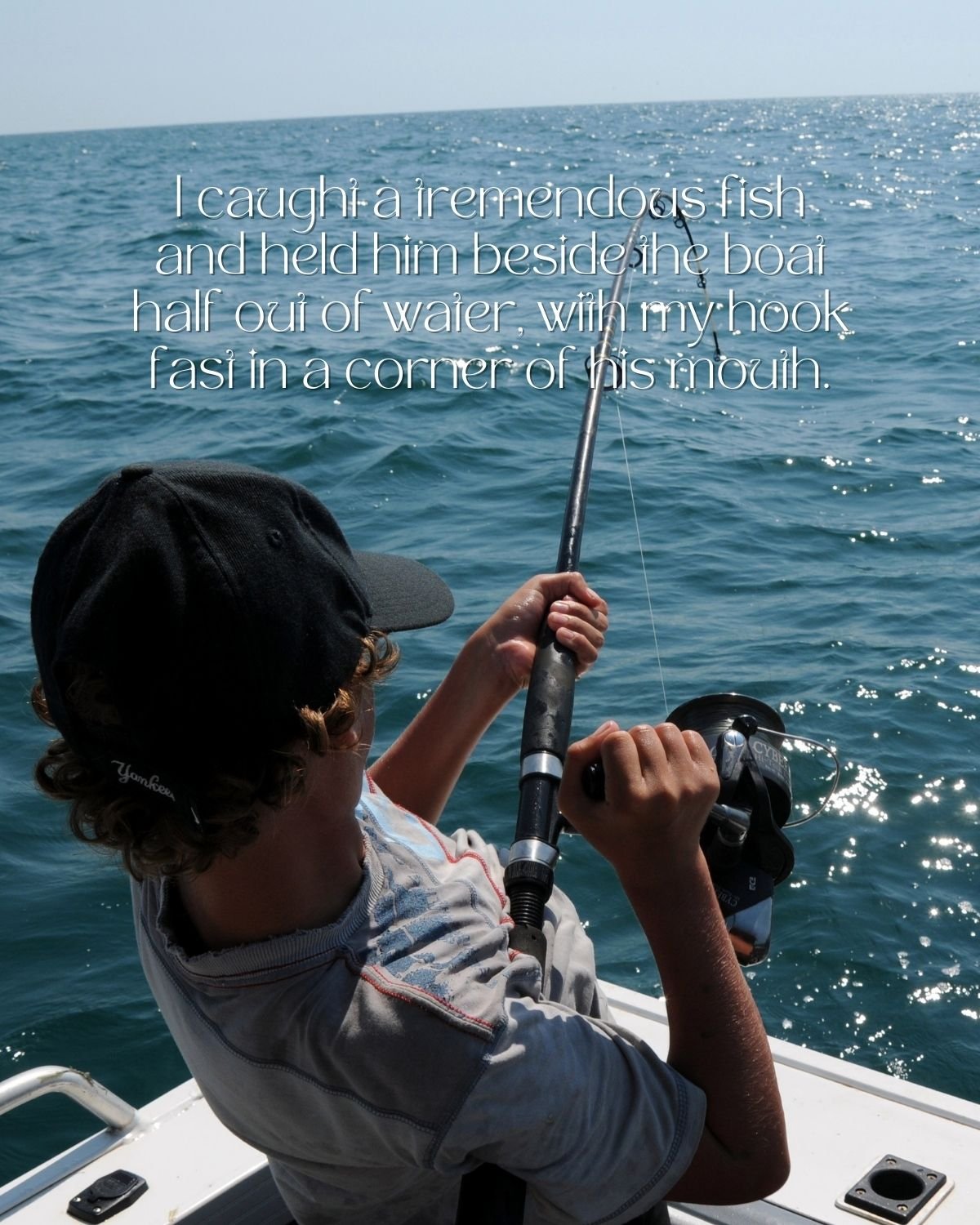

I caught a tremendous fish

and held him beside the boat

half out of water, with my hook

fast in a corner of his mouth.

He didn’t fight.

He hadn’t fought at all.

He hung a grunting weight,

battered and venerable

and homely. Here and there

his brown skin hung in strips

like ancient wallpaper,

and its pattern of darker brown

was like wallpaper:

shapes like full-blown roses

stained and lost through age.

He was speckled with barnacles,

fine rosettes of lime,

and infested

with tiny white sea-lice,

and underneath two or three

rags of green weed hung down.

While his gills were breathing in

the terrible oxygen

—the frightening gills,

fresh and crisp with blood,

that can cut so badly—

I thought of the coarse white flesh

packed in like feathers,

the big bones and the little bones,

the dramatic reds and blacks

of his shiny entrails,

and the pink swim-bladder

like a big peony.

I looked into his eyes

which were far larger than mine

but shallower, and yellowed,

the irises backed and packed

with tarnished tinfoil

seen through the lenses

of old scratched isinglass.

They shifted a little, but not

to return my stare.

—It was more like the tipping

of an object toward the light.

I admired his sullen face,

the mechanism of his jaw,

and then I saw

that from his lower lip

—if you could call it a lip—

grim, wet, and weaponlike,

hung five old pieces of fish-line,

or four and a wire leader

with the swivel still attached,

with all their five big hooks

grown firmly in his mouth.

A green line, frayed at the end

where he broke it, two heavier lines,

and a fine black thread

still crimped from the strain and snap

when it broke and he got away.

Like medals with their ribbons

frayed and wavering,

a five-haired beard of wisdom

trailing from his aching jaw.

I stared and stared

and victory filled up

the little rented boat,

from the pool of bilge

where oil had spread a rainbow

around the rusted engine

to the bailer rusted orange,

the sun-cracked thwarts,

the oarlocks on their strings,

the gunnels—until everything

was rainbow, rainbow, rainbow!

And I let the fish go.

Fun Poetry With Simple Animal References

29. As kingfishers catch fire, dragonflies draw flame

As kingfishers catch fire, dragonflies dráw fláme;

As tumbled over rim in roundy wells

Stones ring; like each tucked string tells, each hung bell’s

Bow swung finds tongue to fling out broad its name;

Each mortal thing does one thing and the same:

Deals out that being indoors each one dwells;

Selves—goes itself; myself it speaks and spells,

Crying Whát I do is me: for that I came.

Í say móre: the just man justices;

Kéeps gráce: thát keeps all his goings graces;

Acts in God’s eye what in God’s eye he is—

Chríst—for Christ plays in ten thousand places,

Lovely in limbs, and lovely in eyes not his

To the Father through the features of men’s faces.

30. Old Cat’s Dying Soliloquy, An

Years saw me still Acasto’s mansion grace,

The gentlest, fondest of the tabby race;

Before him frisking through the garden glade,

Or at his feet in quiet slumber laid;

Praised for my glossy back of zebra streak,

And wreaths of jet encircling round my neck;

Soft paws that ne’er extend the clawing nail,

The snowy whisker and the sinuous tail;

Now feeble age each glazing eyeball dims,

And pain has stiffened these once supple limbs;

Fate of eight lives the forfeit gasp obtains,

And e’en the ninth creeps languid through my veins.

Much sure of good the future has in store,

When on my master’s hearth I bask no more,

In those blest climes, where fishes oft forsake

The winding river and the glassy lake;

There, as our silent-footed race behold

The crimson spots and fins of lucid gold,

Venturing without the shielding waves to play,

They gasp on shelving banks, our easy prey:

While birds unwinged hop careless o’er the ground,

And the plump mouse incessant trots around,

Near wells of cream that mortals never skim,

Warm marum creeping round their shallow brim;

Where green valerian tufts, luxuriant spread,

Cleanse the sleek hide and form the fragrant bed.

Yet, stern dispenser of the final blow,

Before thou lay’st an aged grimalkin low,

Bend to her last request a gracious ear,

Some days, some few short days, to linger here;

So to the guardian of his tabby’s weal

Shall softest purrs these tender truths reveal:

” Ne’er shall thy now expiring puss forget

To thy kind care her long-enduring debt,

Nor shall the joys that painless realms decree

Efface the comforts once bestowed by thee;

To countless mice thy chicken-bones preferred,

Thy toast to golden fish and wingless bird;

O’er marum borders and valerian bed

Thy Selima shall bend her moping head,

Sigh that no more she climbs, with grateful glee,

Thy downy sofa and thy cradling knee;

Nay, e’en at founts of cream shall sullen swear,

Since thou, her more loved master, art not there.”

31. Badger

When midnight comes a host of dogs and men

Go out and track the badger to his den,

And put a sack within the hole, and lie

Till the old grunting badger passes by.

He comes an hears – they let the strongest loose.

The old fox gears the noise and drops the goose.

The poacher shoots and hurries from the cry,

And the old hare half wounded buzzes by.

They get a forked stick to bear him down

And clap the dogs and take him to the town,

And bait him all the day with many dogs,

And laugh and shout and fright the scampering hogs.

He runs along and bites at all he meets:

They shout and hollo down the noisy streets.

He turns about to face the loud uproar

And drives the rebels to their very door.

The frequent stone is hurled where’er they go;

When badgers fight, then everyone’s a foe.

The dogs are clapped and urged to join the fray’

The badger turns and drives them all away.

Though scarcely half as big, demure and small,

He fights with dogs for hours and beats them all.

The heavy mastiff, savage in the fray,

Lies down and licks his feet and turns away.

The bulldog knows his match and waxes cold,

The badger grins and never leaves his hold.

He drives the crowd and follows at their heels

And bites them through—the drunkard swears and reels

The frighted women take the boys away,

The blackguard laughs and hurries on the fray.

He tries to reach the woods, and awkward race,

But sticks and cudgels quickly stop the chase.

He turns again and drives the noisy crowd

And beats the many dogs in noises loud.

He drives away and beats them every one,

And then they loose them all and set them on.

He falls as dead and kicked by boys and men,

Then starts and grins and drives the crowd again;

Till kicked and torn and beaten out he lies

And leaves his hold and crackles, groans, and dies.

32. She sights a Bird—she chuckles

She sights a Bird—she chuckles—

She flattens—then she crawls—

She runs without the look of feet—

Her eyes increase to Balls—

Her Jaws stir—twitching—hungry—

Her Teeth can hardly stand—

She leaps, but Robin leaped the first—

Ah, Pussy, of the Sand,

The Hopes so juicy ripening—

You almost bather your Tongue—

When Bliss disclosed a hundred Toes—

And fled with every one—

33. The Paddock And The Mouse

Upon a time, as Aesop could report,

A little Mouse came to a river side;

She might not wade, her shanks were so short;

She could not swim, she had no horse to ride:

Of verray force behove it her to bide,

And to and fro beside that river deep

She ran, crying with many piteous peep.

“Help over, help over,” this silly Mouse did cry,

“For God’s love, somebody over this brim.”

With that a Paddock in the water by

Put up her head, and on the bank did climb;

Quick by nature could duck, and gayly swim.

With voice full rauk, she said on this manner:

“Good morne, Sir Mouse, what is your errand here?”

“Seeist thou,” quod she, “of corn yon jolly flat

Of ripe oats, of barley, peas, and wheat;

I am hungry, and fain would be there-at,

But I am stopped by this water great;

And on this side I get nothing to eat

But hard nuts, which with my teeth I bore.

Were I beyond, my feast were far the more.

“I have no boat, here are no mariners:

And, though there were, I have no freight to pay.”

Quod she, “Sister, let be your heavy cheer;

Do my counsel, and I shall find the way

Without horse, bridge, boat, or yet galley,

To bring you over safely—be not affeared!

And not wetting the whiskers of your beard.”

“I have great wonder,” quod the silly mouse,

How can thou float without feather or fin?

This river is so deep and dangerous,

Me think that thou should drowned be therein.

Tell me, therefore, what faculty or gyn

Thou has to bring thee over this water?” Than

Thus to declare the Paddock soon began:

“With my two feet,” quod she, “lucken [webbed] and broad,

Instead of oars, I row the stream full still;

And though the brine be perilous to wade,

Both to and fro I row at my own will.

I may not drown, for why?—my open gill

Devoids all the water I receive:

Therefore to drown forsooth no dread I have.”

The Mouse beheld unto her fronsit [furrowed] face,

Her wrinkled cheeks, and her lips wide;

Her hanging brows, and her voice so hoarse;

Her gangly legs, and her harsky hide.

She ran aback, and on the Paddock cried:

“If I know any skill of physiognomy,

Thou has some part of falseness and envy.

“For Clerks say the inclination

Of man’s thought proceeds commonly

After the corporeal complexion

To good or evil, as nature will apply:

A twisted will, a twisted physiognomy.

The old proverb is witness of this: Lorum

Distortum vultum, sequitur distortio morum.”

“No,” quod the Toad, “that proverb is not true;

For fair things oft times are found fake.

The blueberries, though they be sad of hue,

Are gathered up when primrose is forsaken.

The face may fail to be the heart’s token.

Therefore I find this Scripture in all places:

Thou should not judge any man after his face.

“Thought I unwholesome be to looked upon,

I have no cause why I should be found lacking;

Were I else fair as jolly Absolon,

I am no causer of that great beauty.

This difference in form and quality

Almighty God has caused dame Nature

To print, and set in every creature.

“Of some the face may be full flourished;

Of silken tongue, and cheer right amorous;

With mind inconstant, false, and varying;

Full of deceit, and means cautelous.”

“Let be thy preaching,” quod the hungry Mouse;

And by what craft thou make me understand

That thou would guide me to yon yonder land?”

“Thou wait,” quod she, “a body that has need,

To help themself should many ways cast:

Therefore go take a double twined thread,

And bind thy leg to mine with knots fast;

I shall thee teach to swim—be not aghast!—

As well as I.” “As thou,” then quod the Mouse,

“To prove that play it were right perilous.

“Should I be bound and fast where I am free,

In hope of help, now then I shrew us both;

For I might lose both life and liberty.

If it were so, who should amend the scathe?

But if thou swear to me the murder oath,

Without fraud or guile, to bring me over this flood,

Without hurt or harm.” “In faith,” quod she, “I do it.”

She gawked up, and to the heavens did cry:

“О Jupiter! of Nature god and king,

I make an oath truly to thee, that I

This little Mouse shall over this water bring.”

This oath was made. The Mouse, not perceiving

The false engine of this foul, deceitful Toad,

Took thread and bound her leg, as she her bade.

Then foot for foot they lept both in the brim;

But in their minds they were right different:

The Mouse thought of nothing but for to swim,

The Paddock for to drown set her intent.

When they in midward of the stream were went,

With all her force the Paddock pressed down,

And thought the Mouse without mercy to drown.

Perceiving this, the Mouse on her did cry:

“Traitor to God, and mansworn unto me,

Thou swore the murder oath right now, that I

Without hurt or harm should ferried be and free;”

And when she saw there was but do or die,

With all her might she forced her to swim,

And pressed upon the Toad’s back to climb.

The dread of death her strengths gave increase,

And forced her defend with might and main.

The Mouse upward, the Paddock down did press;

While to, while fro, while ducking up again.

This silly Mouse, thus plunged into great pain,

Kept fighting as long as breath was in her breast;

Till at the last she cried for a priest.

As they fought thusly, the Glede sat on a branch,

And to this wretched battle took good heed;

And with a wisk, before any of them wist,

He clutched his claw betwix them in the thread,

Then to the land he flew with them good speed,

Glad of that catch, piping with many a pew:

Then loosed them, and both without pity slew.

Then disemboweling them, that butcher, with his bill,

And peeling the skin, full keenly them flayed;

But all their flesh would scant be half a fill,

And guts also, unto that greedy Glede.

When he had their debate thus settled,

He took his flight, and over the fields flew:

If this be true, ask ye at them that saw.

34. A Popular Personage

‘I live here: “Wessex” is my name:

I am a dog known rather well:

I guard the house but how that came

To be my whim I cannot tell.

‘With a leap and a heart elate I go

At the end of an hour’s expectancy

To take a walk of a mile or so

With the folk I let live here with me.

‘Along the path, amid the grass

I sniff, and find out rarest smells

For rolling over as I pass

The open fields toward the dells.

‘No doubt I shall always cross this sill,

And turn the corner, and stand steady,

Gazing back for my Mistress till

She reaches where I have run already,

‘And that this meadow with its brook,

And bulrush, even as it appears

As I plunge by with hasty look,

Will stay the same a thousand years.’

Thus ‘Wessex.’ But a dubious ray

At times informs his steadfast eye,

Just for a trice, as though to say,

‘Yet, will this pass, and pass shall I?’

35. Dog

The dog trots freely in the street

and sees reality

and the things he sees

are bigger than himself

and the things he sees

are his reality

Drunks in doorways

Moons on trees

The dog trots freely thru the street

and the things he sees

are smaller than himself

Fish on newsprint

Ants in holes

Chickens in Chinatown windows

their heads a block away

The dog trots freely in the street

and the things he smells

smell something like himself

The dog trots freely in the street

past puddles and babies

cats and cigars

poolrooms and policemen

He doesn’t hate cops

He merely has no use for them

and he goes past them

and past the dead cows hung up whole

in front of the San Francisco Meat Market

He would rather eat a tender cow

than a tough policeman

though either might do

And he goes past the Romeo Ravioli Factory

and past Coit’s Tower

and past Congressman Doyle

He’s afraid of Coit’s Tower

but he’s not afraid of Congressman Doyle

although what he hears is very discouraging

very depressing

very absurd

to a sad young dog like himself

to a serious dog like himself

But he has his own free world to live in

His own fleas to eat

He will not be muzzled

Congressman Doyle is just another

fire hydrant

to him

The dog trots freely in the street

and has his own dog’s life to live

and to think about

and to reflect upon

touching and tasting and testing everything

investigating everything

without benefit of perjury

a real realist

with a real tale to tell

and a real tail to tell it with

a real live

barking

democratic dog

engaged in real

free enterprise

with something to say

about ontology

something to say

about reality

and how to see it

and how to hear it

with his head cocked sideways

at streetcorners

as if he is just about to have

his picture taken

for Victor Records

listening for

His Master’s Voice

and looking

like a living questionmark

into the

great gramaphone

of puzzling existence

with its wondrous hollow horn

which always seems

just about to spout forth

some Victorious answer

to everything

36. The Fish

I caught a tremendous fish

and held him beside the boat

half out of water, with my hook

fast in a corner of his mouth.

He didn’t fight.

He hadn’t fought at all.

He hung a grunting weight,

battered and venerable

and homely. Here and there

his brown skin hung in strips

like ancient wallpaper,

and its pattern of darker brown

was like wallpaper:

shapes like full-blown roses

stained and lost through age.

He was speckled with barnacles,

fine rosettes of lime,

and infested

with tiny white sea-lice,

and underneath two or three

rags of green weed hung down.

While his gills were breathing in

the terrible oxygen

—the frightening gills,

fresh and crisp with blood,

that can cut so badly—

I thought of the coarse white flesh

packed in like feathers,

the big bones and the little bones,

the dramatic reds and blacks

of his shiny entrails,

and the pink swim-bladder

like a big peony.

I looked into his eyes

which were far larger than mine

but shallower, and yellowed,

the irises backed and packed

with tarnished tinfoil

seen through the lenses

of old scratched isinglass.

They shifted a little, but not

to return my stare.

—It was more like the tipping

of an object toward the light.

I admired his sullen face,

the mechanism of his jaw,

and then I saw

that from his lower lip

—if you could call it a lip—

grim, wet, and weaponlike,

hung five old pieces of fish-line,

or four and a wire leader

with the swivel still attached,

with all their five big hooks

grown firmly in his mouth.

A green line, frayed at the end

where he broke it, two heavier lines,

and a fine black thread

still crimped from the strain and snap

when it broke and he got away.

Like medals with their ribbons

frayed and wavering,

a five-haired beard of wisdom

trailing from his aching jaw.

I stared and stared

and victory filled up

the little rented boat,

from the pool of bilge

where oil had spread a rainbow

around the rusted engine

to the bailer rusted orange,

the sun-cracked thwarts,

the oarlocks on their strings,

the gunnels—until everything

was rainbow, rainbow, rainbow!

And I let the fish go.

37. All Grass

The eye can hardly pick them out

From the cold shade they shelter in,

Till wind distresses tail and mane;

Then one crops grass, and moves about

– The other seeming to look on –

And stands anonymous again

Yet fifteen years ago, perhaps

Two dozen distances sufficed

To fable them : faint afternoons

Of Cups and Stakes and Handicaps,

Whereby their names were artificed

To inlay faded, classic Junes –

Silks at the start : against the sky

Numbers and parasols : outside,

Squadrons of empty cars, and heat,

And littered grass : then the long cry

Hanging unhushed till it subside

To stop-press columns on the street.

Do memories plague their ears like flies?

They shake their heads. Dusk brims the shadows.

Summer by summer all stole away,

The starting-gates, the crowd and cries –

All but the unmolesting meadows.

Almanacked, their names live; they

Have slipped their names, and stand at ease,

Or gallop for what must be joy,

And not a fieldglass sees them home,

Or curious stop-watch prophesies :

Only the grooms, and the grooms boy,

With bridles in the evening come.

38. View of a Pig

The pig lay on a barrow dead.

It weighed, they said, as much as three men.

Its eyes closed, pink white eyelashes.

Its trotters stuck straight out.

Such weight and thick pink bulk

Set in death seemed not just dead.

It was less than lifeless, further off.

It was like a sack of wheat.

I thumped it without feeling remorse.

One feels guilty insulting the dead,

Walking on graves. But this pig

Did not seem able to accuse.

39. About Animals

Animals are my friends and my kin and my playfellows;

They love me as I love them.

I have a feeling for them I cannot express . . .

It burns in my heart.

I make thoughts about them to keep in my mind.

I warm the cold, help the hurt, play with the frolicsome;

I laugh to see two puppies playing

And I wonder which is which!

General is a dog with blue-black eyes;

They shine . . . there is a love comes from them;

He is filled with joy when he guards me;

His eyes try to speak.

I see his mind through them

When he asks me to say things for him as well as I can

Because he has no words.

40. The Rhinoceros

The rhinoceros walks around, he’s large but makes less noise

And does less damage I am sure than certain girls and boys.

41. Of The Mole in the Ground – a cute underground animal poem

The mole’s a creature very smooth and slick,

She digs i’ th’ dirt, but ’twill not on her stick;

So’s he who counts this world his greatest gains,

Yet nothing gets but’s labour for his pains.

Earth’s the mole’s element, she can’t abide

To be above ground, dirt heaps are her pride;

And he is like her who the worldling plays,

He imitates her in her work and ways.

Poor silly mole, that thou should’st love to be

Where thou nor sun, nor moon, nor stars can see.

But O! how silly’s he who doth not care

So he gets earth, to have of heaven a share!

42. To a Rabbit

Go to the green wood, go

I oft shall sigh for thee,—

And yet rejoice to know,

That thou art sporting free.

Go to the meadows green,

Where summer holds her reign;

When winter spoils the scene

Wilt thou return again?

A shelter thou wouldst find

From every howling storm;

The heart thou leav’st behind

Would still be true and warm.

Why dost thou struggle thus?

Does every balmy breeze

That softly fanneth us,

Tell of the waving trees?

Do yonder happy birds

That sing for thee and me,

For chorus have the words

So precious—”I am free?”

Go then, as free as they,

As light and happy roam

With thy companions gay,

Safe in thy forest home.

There—thou art gone; farewell!

My heart leaps up with thine;

And I rejoice to tell

Thou art no longer mine.

I could not breathe the air

Where pining captives dwell;

My freedom thou wilt share,

With joy then, fare-thee-well.

43. The White Hare

It was the Sabbath eve: we went,

My little girl and I, intent

The twilight hour to pass,

Where we might hear the waters flow,

And scent the freighted winds that blow

Athwart the vernal grass.

In darker grandeur, as the day

Stole scarce perceptibly away,

The purple mountain stood,

Wearing the young moon as a crest:

The sun, half sunk in the far west,

Seem’d mingling with the flood.

The cooling dews their balm distill’d; A holy joy our bosoms thrill’d;

Our thoughts were free as air;

And by one impulse moved, did we

Together pour, instinctively,

Our songs of gladness there.

The green-wood waved its shade hard by:

While thus we wove our harmony:

Lured by the mystic strain,

A snow-white hare, that long had been

Peering from forth her covert green,

Came bounding o’er the plain.

Her beauty ’twas a joy to note;

The pureness of her downy coat,

Her wild, yet gentle eye;

The pleasure that, despite her fear,

Had led the timid thing so near,

To list our minstrelsy!

All motionless, with head inclined,

She stood, as if her heart divined

The impulses of ours,

Till the last note had died, and then

Turn’d half reluctantly again

Back to her green-wood bowers.

Once more the magic sounds we tried;

Again the hare was seen to glide

From out her sylvan shade;

Again, as joy had given her wings,

Fleet as a bird she forward springs

Along the dewy glade.

Go, happy thing! disport at will;

Take thy delight o’er vale and hill,

Or rest in leafy bower:

The harrier may beset thy way,

The cruel snare thy feet betray!

Enjoy thy little hour!

We know not, and we ne’er may know,

The hidden springs of joy and wo

That deep within thee lie:

The silent workings of thy heart,

They almost seem to have a part

With our humanity!

What a concept: wanting to learn from animals. But as humans, we take on so many traits from the other people around us and people also can go into instinct survival mode, and these things don’t always make us the most thoughtful or careful beings. It’s a totally different kind of survival.

So I want to learn from animals sometimes, more than other people.

Take dogs for example. Have you ever stepped on your dog’s tail or paw, and they acted like you didn’t just hurt them? They almost act like they’re apologizing to YOU for being in your way! This is such a gracious way of life that I want to take on in appropriate and healthy doses.

Let’s learn from animals and also have a sweet and lighthearted time reading about them in these cute animal poems.

Animal lover or not, I feel like you’re going to like these poems a lot!

I love a good animal poem. Sometimes they have deeper and cooler meanings behind them, and sometimes they’re just cute pieces of writing about your favorite little furry friends. Or big non-furry ones. Who knows, I won’t make any assumptions about your favorite animal!

There’s so many fun things about animals, the sweet way that they interact with the world, the way that they can be funny without trying, or even funny while trying to be! Have you ever seen a video of an elephant entertaining a crowd? Sometimes I swear they know what they’re doing and love to do it for laughs!

Whatever brought you here for animal poems, I hope you loved each one and have had fun reading about our little buddies. Whether you’re here for kids’ poems or elaborate works of poetry to inspire you, there are so many ways that animals can be incorporated into poetry.

Need some holiday specific ones? When Thanksgiving comes back around, here are 21 funny turkey poems to bring to the table.